In the United States, prepaid wireless services took a while to catch on; while customer demand was certainly there from the beginning, telecoms were somewhat apprehensive about deviating from the tried-and-true service contract and monthly billing arrangements. Eventually, American providers of wireless services gave into demand, and they marketed this option as being more convenient, more flexible, and just as secure as cell phone service contracts.

Unlike other countries where the regulation of prepaid wireless services tends to be more relaxed in terms of requesting information from users, a prepaid SIM account in the U.S. requires the collection of personally identifiable information; moreover, each prepaid customer becomes an account record, one that can be tied to financial information to make it easier to add credit, airtime, and services. With regard to data security, there is no difference between wireless contracts and prepaid arrangements, and this is something that T-Mobile was recently forced to contend with.

Unlike other countries where the regulation of prepaid wireless services tends to be more relaxed in terms of requesting information from users, a prepaid SIM account in the U.S. requires the collection of personally identifiable information; moreover, each prepaid customer becomes an account record, one that can be tied to financial information to make it easier to add credit, airtime, and services. With regard to data security, there is no difference between wireless contracts and prepaid arrangements, and this is something that T-Mobile was recently forced to contend with.

According an official press release issued by T-Mobile on November 22, a data breach affected about 1.12 million prepaid service customers, which represents less than 1.5% of their total user base. The incident occurred in early November, and it looks like a standard cybercrime situation and not an insider attack. Affected customers received SMS notifications about the incident, and they were urged to change their passwords as well as the PIN codes they use for easy account access.

Fortunately, the cyber perpetrators were not able to steal financial records associated with the accounts, which means that credit cards and social security numbers were not compromised; nonetheless, the stolen records include names, phone numbers, account numbers, and billing addresses. In the hands of cybercrime groups dedicated to identity theft, this type of information can be very dangerous.

Earlier this year, hackers were somehow able to access customer records of Sprint wireless subscribers, and they did so by exploiting a vulnerability on a website that caters to owners of Samsung smartphones. Similar to the T-Mobile incident, financial records were not accessed, and this is probably related to compliance with Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards.

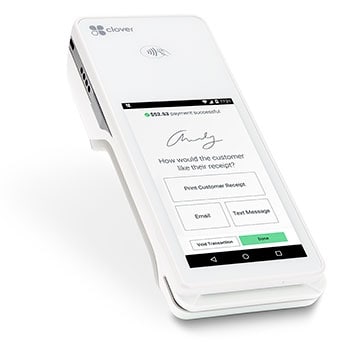

For the payment processing industry, prepaid wireless services have become a substantial segment of their business. Unlike wireless contracts, which are mostly settled once per month and sometimes just once per year for customers seeking deep discounts, topping up prepaid smartphones with voice minutes or blocks of data is something that they may do a couple of times each week, and even more often when carriers send out notifications with coupons and special deals. The most privacy-conscious will only “top up” their cell phones with cash; however, quite a few end up linking credit and debit cards for convenience.

The top 25 imitated brands were examined in Vade Secure’s report, and it also shined a light on many of the tactics employed by the phishers as they pose as these various websites in an attempt to break security and obtain users’ data and information. Ever since the Vade Secure reports first began in the second quarter of 2018, Microsoft has had the privilege of owning the number 1 spot when it comes to the company most targeted for phishing. As of the first quarter of 2019, however, Microsoft lost that top spot to PayPal. Online streaming service Netflix, with its 158 million subscribers worldwide, is next in line at 3rd place.

The top 25 imitated brands were examined in Vade Secure’s report, and it also shined a light on many of the tactics employed by the phishers as they pose as these various websites in an attempt to break security and obtain users’ data and information. Ever since the Vade Secure reports first began in the second quarter of 2018, Microsoft has had the privilege of owning the number 1 spot when it comes to the company most targeted for phishing. As of the first quarter of 2019, however, Microsoft lost that top spot to PayPal. Online streaming service Netflix, with its 158 million subscribers worldwide, is next in line at 3rd place. Beyond

Beyond

Until Ant Financial, the Alibaba affiliate that runs Alipay’s platform, made the following announcement earlier this month, users of the Alipay platform were required to have a Chinese bank account. Until now, that is, with Alipay announcing a program called “Tour Pass” through which the company will introduce a version of the Alipay app that will launch and feature full support for international debit and credit cards. Once users have download the Alipay app onto their iOS or Android device, they will be able to use their phone number to set themselves up for the international version of the app.

Until Ant Financial, the Alibaba affiliate that runs Alipay’s platform, made the following announcement earlier this month, users of the Alipay platform were required to have a Chinese bank account. Until now, that is, with Alipay announcing a program called “Tour Pass” through which the company will introduce a version of the Alipay app that will launch and feature full support for international debit and credit cards. Once users have download the Alipay app onto their iOS or Android device, they will be able to use their phone number to set themselves up for the international version of the app. Rather than pay interchange fees directly, businesses pay credit card processors according to these tiered rates. The processors then pay the interchange fees on behalf of the businesses. Instead of listing the actual interchange fees, credit card processors list only the qualified, mid-qualified, and non-qualified rates under tiered pricing.

Rather than pay interchange fees directly, businesses pay credit card processors according to these tiered rates. The processors then pay the interchange fees on behalf of the businesses. Instead of listing the actual interchange fees, credit card processors list only the qualified, mid-qualified, and non-qualified rates under tiered pricing.